The avatar might be a cockerel, a razor or, most likely, a beautiful Eastern European or Latino woman. Behind the avatar, there might be a human, a bot or some combination of the two.

With Zimbabwe’s ‘varakashi’ it is hard to be sure of much.

Their job, at least, is clear cut: disrupt online debates and stymie criticism of President Emerson Mnangagwa and his government. The president himself gave this faceless group the name ‘varakashi’, which is the word for ‘destroyers’ in the Shona language. During the last presidential campaign, at a rally of his ruling Zanu-PF party in May 2018, Mnangagwa — perhaps indiscreetly — spoke to the younger members of his audience:

“Some of us are old; you are still youthful and masters of technology. The new digital chatrooms are war rooms. Jump in and hammer party enemies online. Don’t play second fiddle.”

Today, the varakashi are on call 24 hours a day. Whether an emerging online conversation is about failing hospitals or looming starvation, the varakashi are quickly out of the blocks. New Twitter accounts — with deceptive avatars — are registered in under two minutes, then the disruption begins. Chat threads are spammed, and eventually slowed, with a barrage of hyperlinks. Or they are driven off-topic by volleys of disingenuous interjections.

Hammer them online

Steve Hanke, professor of applied economics at John Hopkins University and director of its joint Troubled Currencies Project with the Cato Institute, persistently challenges the Zimbabwean government’s inflation figures, believing they are falsified for political purposes. When he publishes a critical report, varakashi flood related online chat threads with bot links and often vicious personal attacks.

Some of the varakashi are probably volunteers — Zanu-PF supporters willing to give their time for free. Since Mnangagwa officially recognized them, suspicion has grown that some of them are paid by the government. The economics of this belief are straightforward: government statistics show that, as of 2014, 95% of the population had no formal employment and survived as street hawkers. The $80 a month that is rumoured to be the going rate for varakashi work would be attractive, and it would suit the Zimbabwean government too.

Fertile ground for spreading fake news

A connected and financially desperate population makes Zimbabwe a fertile ground for organised spreading of disinformation. In the first quarter of 2018, Internet penetration reached 52%, with mobile phone penetration at 85%.

The opportunity is growing and the varakashi’s range of methods is widening.

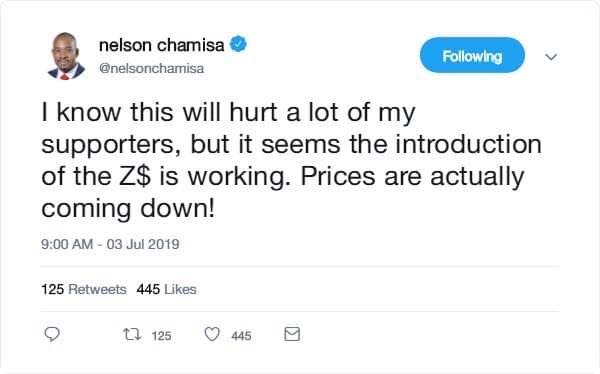

In May 2019, screenshots posted on Twitter appeared to portray Zimbabwe’s opposition leader, Nelson Chamisa, gloating about having monetized the country’s tribal divisions. There was another attempt to undermine the head of the Movement for Democratic Change in July, with a Photoshopped tweet that suggested he supported Mnangagwa’s controversial and unilateral replacement of the US dollar as the national currency with the Zimbabwean dollar.

For added ‘authenticity’, such fabricated posts are often supported by fake replies.

Dear brother @TrevorNcube, you are fighting a good battle on local currency front! But some in the regime have gotten so desperate such that they are now photoshopping @nelsonchamisa’s twitter account in search of legitimacy! This young leader’s endorsement must be important hey?

The varakashi’s horizons have also expanded. In May 2019, a prominent pro-government tweeter, @CdeNMaswerasei (Never Maswerasei), launched a Change.org petition calling on the UK’s University of Kent to cut ties with Alex Magaisa, a law professor and human rights campaigner who helped write Zimbabwe’s constitution and publishes the country’s most-read weekend politics magazine, The Big Saturday Read. Maswerasei accused Magaisa of peddling “outright lies & propaganda” about the Zimbabwean government. To date, the petition has mustered only a few signatories, but the varakashi’s actions are not always so harmless.

Online fake news, real life consequences

In launching a rival Change.org petition in support of Magaisa that has attracted almost 10 times as many signatures, Lee Kakomarara warned:

“After completely decimating freedom of speech and human rights in Zimbabwe. The ruling party has come up with sinister attempts to spread their gags across international boundaries, through its intelligence organizations, stalking and attacking political activists and human rights defenders online.”

Indeed, the varakashi’s online smear campaigns can have real-world consequences.

Again during May 2019, seven Zimbabwean activists were arrested and charged with treason after they returned from the Maldives, where they had attended a training event organised by the Center for Non-Violence Action and Strategies (Canvas). Prior to the arrests, a flurry of posts from varakashi accounts had accused the activists of travelling abroad for nefarious reasons.

Those activists have been reined in but, as Zimbabwe’s most successful media entrepreneur, Trevor Ncube, has said:

“Social media mischief here knows no boundaries.”

Source: iAfrica