IN 2000, Zimbabwe’s government expropriated white farmers without compensation. Hyperinflation and food shortages followed. Now the South African government is discussing a similar law. Do the same risks lie ahead?

On a dusty road in eastern Zimbabwe, Rob Smart (70) can barely get out of his van as dozens of friends and farm workers run to welcome the white farmer back to his land. He and his son Darryn had been evicted from their property six months ago, land which was then given to a top cleric with ties to the former dictator Robert Mugabe. Smart is one of thousands of white Zimbabwean farmers who were expropriated without reimbursement since Mugabe’s “fast-track” land reform was implemented in 2000. The annnouncement by new president Emmerson Mnangagwa that landowners would be given back their property meant he could return home.

Just a few hundred kilometers (miles) further south from the Smart farm, history appears to be repeating itself. South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress ( ANC) is discussing amending the constitution to implement land expropriation without compensation. South African farmers are alarmed: “Expropriation without compensation is an economic time bomb”, the South African agricultural industry association AgriSA stated in a tweet. If the country were to follow the example of Zimbabwe, the consequences could be dramatic, not only for its mostly white farmers.

Zimbabwe’s economic downfall

“The biggest risk to production would be if the threat of disorderly or rapid expropriation caused capital flight or failure to invest in the land,” says Mike Albertus, assistant professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. In Zimbabwe, this is exactly what happened. Where there was once a flourishing agricultural sector, with an abundance of wildlife and natural resources, the country is now in need of food imports to feed its population, of which over two thirds live in poverty. But food shortages are not the only factor which made the Zimbabwean government reverse around its former expropriation policies. Extreme hyperinflation followed in the years of Mugabe’s land-grabbing, destroying pension funds and bringing foreign investment to a halt. But how did unfunded expropriation contribute to hyperinflation and eventually to economic downfall?

Although taking land and giving it to the disadvantaged without compensation to the owners sounds like an easy solution to achieve income equality, it’s not that simple, says property rights lawyer Elmien Du Plessis from North-West University in Pretoria. In a situation where indebted farmers with mortgages on their land lose it without compensation, they will no longer be able to pay back their loans. Banks would make losses, and if many ex-owners found themselves in the same situation, it could trigger a banking crisis, setting off a spiral of hyperinflation with disastrous consequences for the whole economy.

What lies ahead in South Africa?

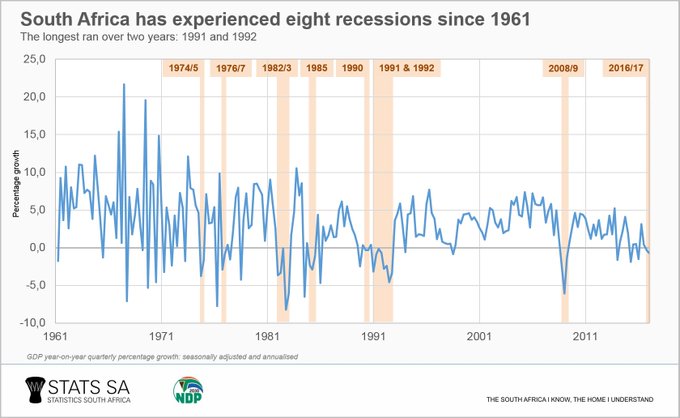

South Africa has many of the factors which could speed up such a hyperinflation cycle. The country’s Gross National Product has been in decline since 2011, and unemployment peaked in 2017, with over one quarter of the working population jobless. Additionally, the government’s debt levels are rising and are becoming increasingly more expensive to finance, given that the government’s debt-reliability has just been downgraded by two rating agencies. Nevertheless, Albertus warns against jumping to quick conclusions: “Zimbabwe was a dictatorship under Mugabe, whereas South Africa is a democracy. And the plurality of representation that democratic institutions afford makes it very difficult to implement large-scale and highly redistributive land reform.” According to Albertus, history has taught South Africa that a slow program of land redistribution is better for the economy than a Mugabe-style fast-track land confiscation program.

Land injustice since independence

But despite the general consensus not to repeat Zimbabwe’s economic disaster, few people disagree that land ownership needs to be reformed in South Africa. “At the end of apartheid [in 1994], 60,000 white farmers held 86 percent of all farmland. 13 million blacks held the remaining poor-quality land” Albertus told DW. From 1994 to 2007, only 4.2 million hectares (around 10 million acres) of land were passed to blacks through the willing-seller-willing-buyer principle, about a tenth of the government’s initial target. “But the funds simply aren’t there to transfer enough land to black farmers with market-value compensation”, Albertus said. But if funds are unavailable, the question is how land reform can be implemented in a way that it reduces disparity without damaging the economy.

Economic realities versus social justice

In the opinion of property rights lawyer Du Plessis, fair land reform lies in a compromise between the protection of arbitrary state interferences and the basic human right of access to resources. Owners of big estates will have to make compromises, accepting redistribution under market value, she says “but zero compensation can only be just and equitable in very limited circumstances, for instance, a small piece of land for a graveyard.” Albertus agrees, arguing for a light form of land redistribution in which compensation standards would be loosened, but not eliminated, with the help of an international organization such as the World Bank.

Rob Smart has experienced such a compromise: His family has given up more than 90% of their arable land since they built up the farm in the 1930s. But now that he is back on his land, he is optimistic that what is left will continue to be cultivated by himself and his son in the years to come. – DW